Institutional Neutrality in a Time of Genocide

New article published by Critical Inquiry: In the Moment

An article I wrote reflecting on the University of Chicago solidarity encampment has been published on Critical Inquiry’s blog, “In the Moment.” Reproduced in its original form below, it can be accessed in published form here.

********

I want to begin these reflections with an episode I experienced as part of the UChicago United for Palestine (UCUP) negotiating team. Sitting across the table from President Paul Alivisatos, our team was asked what the University administration could do to build trust with student protestors and move toward a negotiated ending of the quad encampment. As a step in this direction, we proposed that Alivisatos issue a University statement opposing Israel’s campaign of scholasticide in Gaza – that is, its systematic destruction of Gazan universities and targeted assassination of Gazan academics. Given the University’s professed commitment to defending free expression “throughout the world” and to “supporting the global academic community in times of great need,” we thought this a fairly uncontroversial proposal. There could scarcely be a greater threat to free expression and academic freedom, after all, than the wholesale destruction of a people’s higher education system.

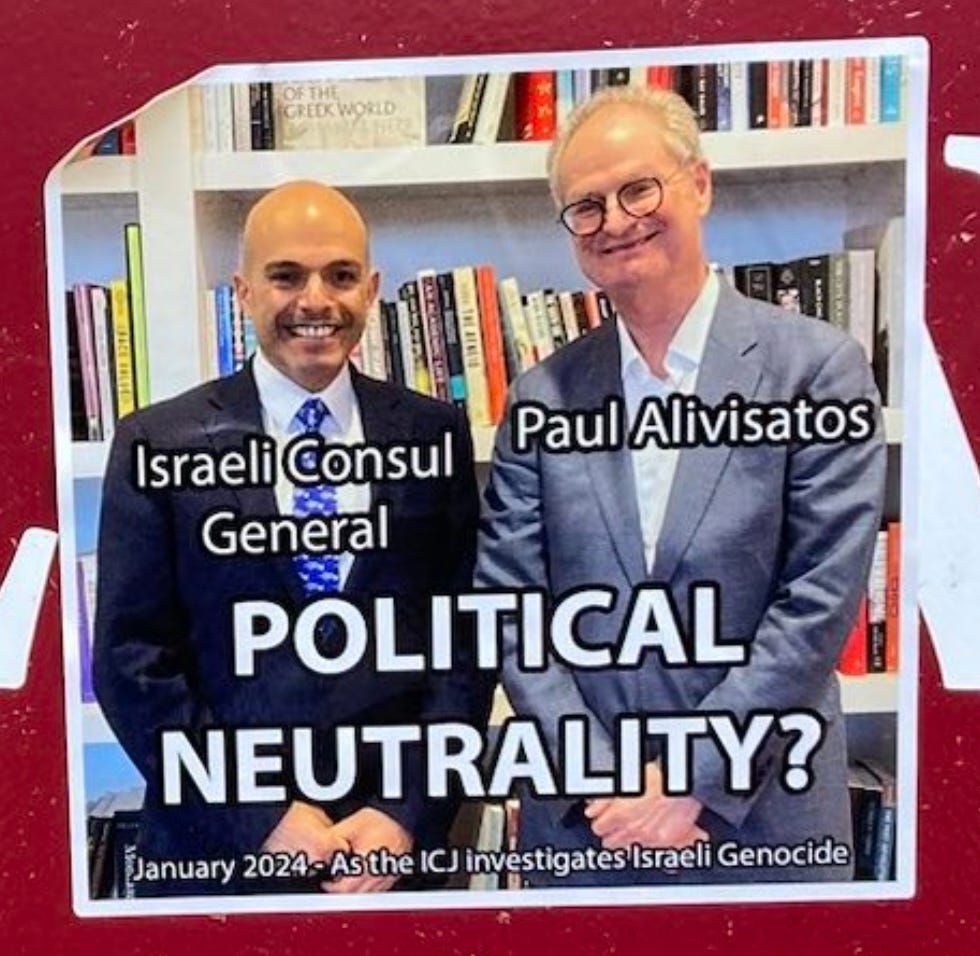

Alivisatos disagreed. Not only, in fact, did he dismiss the idea of making a public statement about Israel’s scholasticide; he refused to concede as a factual matter that Gazan universities had been bombed at all. The problem was not that Alivisatos disbelieved or did not know that such bombings had occurred. (When offered videographic proof, he dismissed it as irrelevant.) Rather, the problem was Alivisatos’ insistence that for him to acknowledge the mere existence of these bombings – even privately, even with evidence, even off the record – would be to take a “political position” and thereby compromise the University’s policy of “institutional neutrality.” After all, Alivisatos explained, there are “people who would disagree” with the facts in question.

At one level, Alivisatos’ position is self-evidently absurd. While the University’s Kalven Report does urge administrators to refrain from “expressing opinions on the political and social issues of the day,” it nowhere prevents them from acknowledging basic facts about the world. (There are “people who would disagree” with the reality of anthropogenic climate change, for example, but that does not prevent the University from recognizing it.) In certain “extraordinary instances,” moreover, the Kalven Report not only permits but explicitly urges the University to oppose socio-political measures that threaten its “values of free inquiry.” This has been the operative logic behind statements the University has readily issued about the invasion of Ukraine, affirmative action, Trump’s immigration policies, and a range of other politically charged issues. Consistency would demand that the same logic be applied to Israel’s scholasticide in Gaza.

Compelling as it may be to highlight the University’s double standards, however, there is something potentially short-sighted about this approach.1 For while it is true in the abstract that facts about Palestine are no more “political” than, say, facts about Ukraine, it is crucial to stress that the University does not exist in the abstract. The “supposedly hermetic world of higher education,” as Steven Salaita reminds us, is “in fact symbiotic with the real world.” Situated among existing concentrations of corporate and political power and predominantly governed by ruling-class trustees, corporate universities process and reproduce the same “prejudices,” “market conditions,” and “geopolitical common sense” at play in other U.S. industries. This context is crucial for understanding what forms of speech these universities do and do not treat as “political.” For the University of Chicago, as for those in power generally, speech is most political when it threatens to disrupt existing power-structures and ideological truisms, least political when it reinforces them.2 Expressions of sympathy for Ukrainians suffering a “devastating humanitarian crisis” as a result of Russia’s “ongoing invasion,” for example, threaten neither the material interests nor the geopolitical ambitions of the U.S. ruling class. The University therefore classifies such statements not as political speech but as displays of student care and basic human decency. Nor does the University consider hosting the Obama Presidential Center to be a political act – a position that many Libyans, Yemenis, and others would no doubt find bizarre and infuriating. Glorifying the Obama presidency is, at this point in time, a politically safe act, one wholly unthreatening to the status quo. It is therefore – from the University’s perspective – not a political act at all.

Speech about Palestine, however, is a different story. If there is one thing Palestine is not, it is “politically safe.” Indeed, merely mentioning Palestine by name is enough to ruffle certain ruling-class feathers – which is presumably why Alivisatos has refused to do so publicly. This situation has little to do with the Palestinians themselves and everything to do with the central place Israel occupies in the ecosystem of U.S. power. There is nothing mysterious or particularly surprising about the fact that it occupies this position. Since the 1970s, Israel has functioned as a strategic outpost for both domestic and imperial U.S. interests, ranging from weapons manufacturing to energy production to the maintenance of regional U.S. hegemony. This being the case, Israel’s centrality to U.S. interests owes neither to lobbyists nor primarily to a deep ideological commitment to Zionism on the part of U.S. elites, but to the fact that Israel has been effectively annexed into the corporate and political power-structure upon which the ruling class (and the University) depends. To voice support for Palestinian liberation – or even to acknowledge basic facts about Palestinians’ oppression at Israel's hands – is therefore to threaten not only Israeli colonialism, but also the U.S. status quo in which both Israel and the University participate.

It is against this backdrop, I would like to suggest, that we can best understand the hostility with which the University of Chicago and other U.S. universities have responded to the ongoing student intifada in support of Gaza.3 The fundamental problem is not that these universities operate with double standards, refusing to support Palestinians while being happy to support Ukrainians. More fundamentally, the problem is that U.S. universities operate all too consistently by a single standard: fidelity to the status quo dictated by U.S. power, no matter what form it takes.

For the past 230 days, this status quo has taken the form of genocide in Gaza.4 Contrary to public perceptions, the U.S. has not merely been complicit in this genocide but has actively presided over it. Since the start of Israel’s onslaught, the U.S. government has sent it more than 100 distinct arms shipments, gifted it more than $18 billion in unconditional military aid, bombed multiple countries in its support, slashed funding for UNRWA, and vetoed no less than four UN Security Council resolutions demanding humanitarian pauses and ceasefires. Israeli officials, for their part, have candidly admitted that their Gaza onslaught could not continue without U.S. support. What we are witnessing, then, is not simply an Israeli genocide, but a U.S.-Israeli genocide. Whether most of us realize it or not, the blood of Gaza’s children is on the hands of U.S. citizens and institutions no less than it is on the hands of Israeli society.

In such a situation – what Hannah Arendt called the “intrusion of criminality into the public realm” – there can be no neutral option: “whoever participates in public life at all, regardless of party membership or membership in the elite formations of the regime, is implicated in one way or another in the deeds of the regime as a whole.” It is this basic truth that student protestors have been insisting upon for months, despite their administrators’ cynical attempts to evade it. In calling for divestment from Israel’s genocide, they have in effect been calling on their administrators to cease operating as cogs in the machinery of U.S. power and instead to act, finally and for once, as moral and institutional stops to it. Hiding behind the rhetoric of “institutional neutrality” will not deliver administrators from the burden of this decision. On the contrary, as Jasbir Puar points out, it will only deepen their culpability: “It is precisely by denying culpability or assuming that one is not implicated in violent relations toward others, that one is outside them, that violence can be perpetuated.”5

Even now, 230 days into this genocide, a clear call is emanating from the Gaza ghetto: never again. There can be no neutral option in the face of this call – least of all on the part of academic institutions already invested in Israel’s arms suppliers and implicated in Gaza’s suffering. For administrators like Alivisatos to justify their ongoing silence and inaction in the name of “institutional neutrality” is merely to confess their abiding allegiance to the status quo, i.e., to U.S.-Israeli genocide. This in itself is a political decision, albeit an ugly and cowardly one. Ultimately, the question facing Alivisatos and administrators around the country is not whether they will act politically in response to Gaza’s call, but how they will do so: as functionaries of ruling-class power or as principled human beings. Granted, the latter choice may involve a degree of personal sacrifice and career risk – but has that stopped students from making it?

I say this self-critically, who has adopted this approach regularly in recent months.

This is not to deny that the University of Chicago makes a concerted effort to limit its political speech even within the boundaries of what existing power-structures deem acceptable; this is part of its distinctive brand, after all. But it is to point out that the University is dead-set against engaging in speech that exceeds those boundaries. As I explain below, speech about Palestine is a paradigmatic case of such “excessive” speech.

Needless to say, corporate media outlets, police departments, and U.S. lawmakers have played their parts in this hostility as well.

The scale and horror of this genocide are almost impossible to overstate. More than 36,300 Palestinians have been slaughtered, including 15,000 children. At least 10,000 others are missing, most presumed dead under the rubble. Still another 80,000 have been injured, many quite severely, in a territory that has been robbed of all fully functioning hospitals. 1.1 million Palestinians now suffer “catastrophic food insecurity” as a result of Israel’s systematic denial of food and water, a policy that has already led to the deaths of at least 28 children by starvation and dehydration. In an effort to increase starvation-related deaths, Israeli soldiers have repeatedly bombed aid convoys, massacred Palestinians rushing to food trucks, and assisted settlers in preventing new trucks from entering the territory at all. Other soldiers have contributed to Israel’s campaign by, among other things, executing Palestinians in front of their families, torturing them in detention camps, massacring them inside hospitals, drone-striking them for sport, and dumping them in mass graves. Far from being isolated acts by rogue soldiers, these atrocities figure into the Israeli government’s systematic effort to eradicate the very foundations and future of Palestinian life in Gaza. Already by late December, for example, Israel had destroyed or damaged 77% of the territory’s healthcare facilities, 211 of its mosques and churches, 195 of its heritage sites, half of its roads, and 60% of its educational facilities. By late March, it had destroyed more than 40% of Gaza’s farmable land and 70% of its homes as well. Now, in open defiance of the International Court, it is hastening toward the genocidal climax of its campaign in Rafah.

Puar’s comments echo those made by James Baldwin in a famous letter to his nephew: “I know what the world has done to my brother and how narrowly he has survived it and I know, which is much worse, and this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it. One can be–indeed, one must strive to become–tough and philosophical concerning destruction and death, for this is what most of mankind has been best at since we have heard of war; remember, I said most of mankind, but it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.” I first encountered the quotes by Puar and Arendt in Michael Rothberg’s The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators.

this is incisive and devastating.